Once Ridiculed As ‘Quackery’, More And More People Are Now Getting Drawn To Phrenology

The doctrine was developed by German physiologist Franz Joseph Gall around 1800

Once Ridiculed As ‘Quackery’, More And More People Are Now Getting Drawn To Phrenology

With an increasing number of aircraft being serviced and maintained domestically, there is a corresponding rise in the requirement for locally manufactured parts to support these operations

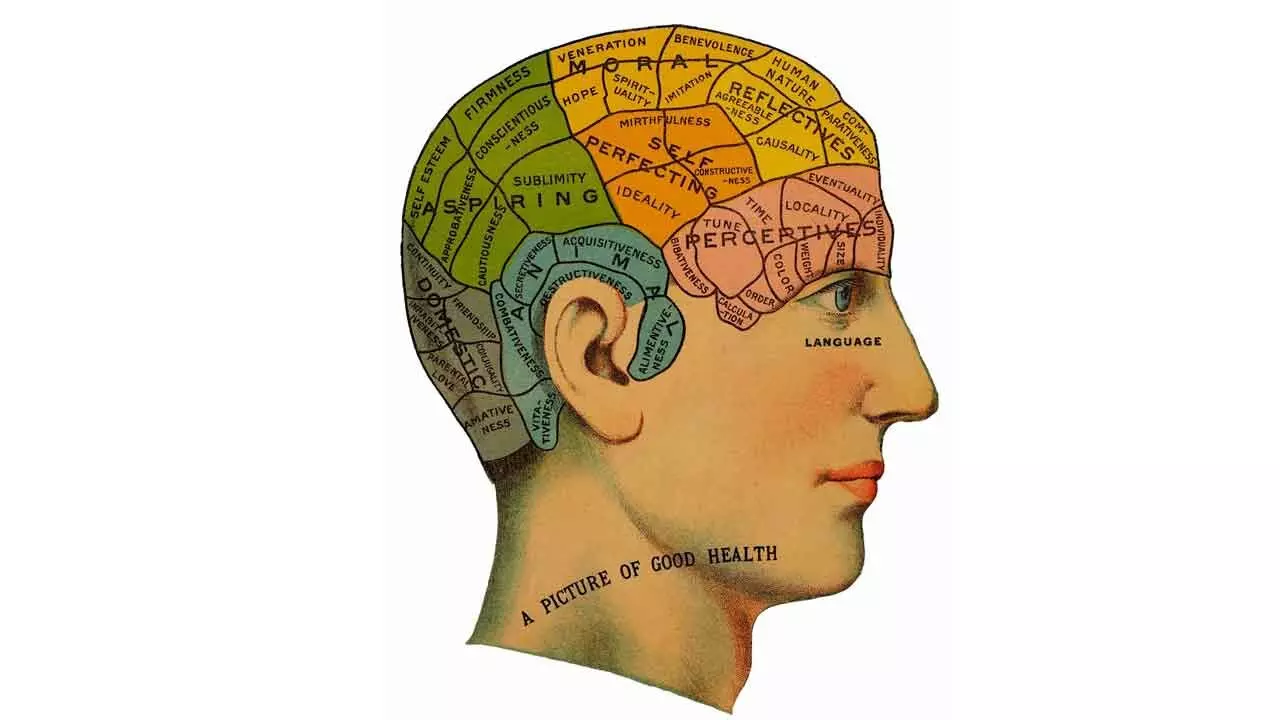

It's hard to imagine now, but people once believed that the bumps on your head could reveal your personality. For one thing, it's so hard to locate the bumps on your head, let alone the thirty or so bumps that phrenologists said could be discerned.

So why was phrenology such an attractive idea for such a long time? Phrenology was the belief that the brain's activity could be studied by examining the bumps on the skull, in places where the brain pushed outwards.

Initially, after German physiologist Franz Joseph Gall developed the new doctrine around 1800, it was a subject of serious scientific debate. But it was soon labelled quackery by the academic elite. But that wasn't the end of phrenology.

In fact, it became more popular in the 19th century, thanks to physician Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, who wrote books and delivered public lectures in Britain and France – focusing less on skulls and brains, and more on reading the living people.

It remained a popular pastime for more than a century, mainly in English-speaking parts of the world but also outside it, for example in China.

Part of the appeal of phrenology was that it gave people a vocabulary to understand themselves and others. With urbanisation and a growing middle class, outside rigid class and religious structures, people were curious about new ways to categorise humankind.

In the city, you wouldn't necessarily know everyone nearby or even your neighbours, so your place in society was less determined. This may have led to more freedom but also to insecurity about what your and everyone else's place was.

Phrenology was a new way of classifying others. But it was not only meant to study others, it was also a way to know yourself, just like diary writing which also gained popularity in this period. With the help of phrenology, people could now see themselves as having an individual self, reflected in the shape of their head.

Those interested could go to a lecture or read a book about phrenology or – if you lived in New York – visit the Phrenological Cabinet, a display of skulls, busts and portraits. If you really wanted to learn something about yourself, you asked a phrenologist for an examination.

In the US this would cost you about half a dollar today. Many popular phrenologists in the UK and the US offered readings. They were often itinerant; setting up shop in hotel rooms or at Brighton Pier in southern England.

After a reading, clients sometimes received a written assessment, but more usually received a cheaper standardised chart that detailed their characteristics. On it, they received a score for typical phrenological characteristics such as adhesiveness (or friendship), spirituality, benevolence and time. The score was based on the phrenologist's approach. They tended to gauge the size of the bumps in relative size, compared to your other bumps and to other people's bumps.

They claimed that this was a scientific approach, but it gave phrenologists a great deal of freedom in interpretation. And my analysis of about 160 charts between 1840 and 1940 showed that every single person who received a chart scored above average in most if not all traits. The positive results partly explain the appeal of a visit to the phrenologist. Barnum effect:

Another explanation, writes history professor Michael Sokal, is the Barnum effect. This is the tendency of people to rate descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored for them as accurate. In fact, they are often so vague and general that they would apply to almost all people.

Many people, for example, would agree with the suggestion that they are of above-average intelligence but also experience anxiety and self-doubt sometimes. And, indeed, in my collections of phrenological charts, the trait that on average gets the lowest score was “self-esteem”.

If only you work a bit on your self-esteem, is the implicit message, you can be an even better version of yourself. Phrenologists were often deterministic when they judged criminals or non-white people, based on the skulls or busts they had of people from these categories. Their irregular features or skull shapes apparently condemned them to a life in prison or slavery. But they took a different approach to the middle-class visitors of their offices.

The character trait of “destructiveness”, for example, was seen the trait of a murderer, but for a middle-class individual was usually explained as energy for overcoming difficulties.

According to phrenologists, everyone could play a role in their destiny and people could use their self-knowledge for improvement. Taking time to reflect on the relationship between cause and effect, for example, could slowly increase the size of your “causality” bump, phrenologists said. Early 20th-century phrenologist Stephen Tracht said that it took three weeks for a child, three years for a young man, and more once you were 45 or 50, to develop a specific part of the brain. These practices show how in phrenology self-knowledge and self-improvement came to be seen as two sides of the same coin.

Not everyone would have accepted their phrenological assessment as an absolute truth, while customers often took only the information from it that they liked.

Either way, phrenology did become part of people's vocabulary and with it the message that with the right tools, they could become a better version of themselves.

(The writer is associated with Leiden University)